14 October 1943 - 291 US Army Air Force (USAAF) heavy bombers took off from England to attack a Ball Bearing factory in the heart of Germany. The goal was to destroy the Nazi war machine’s fighting ability and means of war production. As the bombers flew deeper into enemy territory their supporting escorts had to return to England due to the fighters’ shorter range. The unescorted bombers were vulnerable to enemy fighters and paid a heavy price. 60 did not return leading to a loss rate of over 20% thus cementing October 14, 1943 as ‘Black Thursday’. The ten crewmen on each of those planes had to survive 25 (later pushed to 30) missions to return home. They could not sustain losses like this indefinitely.

But they wouldn't have to for long. Within a year similar missions could be completed with far fewer casualties - often well below 5%.

The above plot shows raids for the Eighth Air Force during two time periods; on the left the second half of 1943 and the right July - Mid August 1944. Each point represents a raid’s distance and percentage of planes that did not return back to base. This does not count bombers scrapped after landing due to heavy damage. Nor does it account for wounded, killed, or POWs in a mission (even if a plane came back not all of the crew did).

In the chart on the left one can see a fairly strong if imperfect relationship between distance (I chose London as a starting point but airfields were scattered throughout southern England) and bomber losses. The second chart on the right shows this relationship is far less prevalent. The average loss rate of planes during the second half of 1943 was around 3.9% compared with 1% loss rate in the summer of 1944. Using these as proxies for survival probabilities and 30 as the number of missions required before a crew member finished a tour of duty the probability a member came home went from 30% to 74%. How did the loss ratio decrease by so much during this period?

The consensus story of those two plots goes something like this: after Black Thursday USAAF operations suspended long range attacks into Germany until a fighter was capable of escorting the bombers. Enter the P-51 Mustang.

| A P-51 with drop tanks. Notice the Swastikas underneath the canopy - the only acceptable place to display a swastika - each indicating an aerial victory. Having met the criteria of five aerial victories this pilot has earned the moniker of “ace”. |

An American aircraft (with an English designed engine) it was capable of flying to Berlin and back. Not only did it have the necessary range but also outclassed the German interceptors of the period. The P-51 was therefore able to ‘break the back’ of the Luftwaffe and gain air supremacy over europe. This allowed USAAF bombers to go into Germany and beyond without heavy losses.

But the claims of the P-51’s importance often goes farther than that. With air superiority the Allies launched the D-Day landings of Normandy unencumbered. And with Allies now fighting Germany in the west a Nazi Defeat was inevitable. A causal line of reasoning is therefore established between the P-51 and the ultimate destruction of Nazi Germany. Perhaps this is why - somewhat uniquely for a fighter plane - it’s achieved something of a totem status.

But did the P-51 Mustang “break the back” of the Luftwaffe? This post will go over the consensus history of operations between the summers of 1943 and 1944. It will go over Mission Level data. An index is created of German Pilot Strength over time.

This follows the history laid out by McFarland and Newton. But it seems most histories are similar to this and conclude that the Luftwaffe was defeated prior to D-Day.

Strategic Bombing and Pointblank

Air power was still relatively new at the beginning of WW2. It wasn’t clear at the outset how best to use it in a military conflict. Broadly speaking there were two ways of thinking how the airplane could affect the course of the war.

This first and most obvious use of airpower was as a tactical force. A precision armaments system that can provide ground support in real time to assist tank and infantry forces. The Germans seized on this use of airpower as a form of ‘mobile artillery’ with devastating effectiveness.

In contrast the English and American Armies focused more on Strategic Bombing. Instead of focusing and directly influencing a battle the bombers would fly deep into enemy territory destroying the means of waging war. The target wasn’t tanks and enemy defenses but enemy factories, oil refineries, transportation networks, and even civilian populations. However, an enemy has never been subdued by strategic bombing before. The USAAF got their chance to see whether they could destroy the enemy from the air with Operation Pointblank.

To prepare for the D-Day Landings in summer of 1944 the Allied command issued the Pointblank Directive in June 1943. The objective was to destroy German Morale and ‘capacity for armed resistance’. It was to do this by imposing ‘heavy losses on Germany day fighter force’ and draw German fighters ‘away from Russian and Mediterranean theatres of war’. Once completing the objective the heavy bomber forces would be put to use in a supportive role of the D-Day in the Spring of 1944.

For a brief overview of tactics in the European Air War see here.

Attrition Warfare

Between the summer and through the fall of 1943 US bombers attacked German factories with high losses. After regrouping forces in late 1943 the allied offensive continued in early 1944. The new P-51 Mustangs were thrown into combat as soon as they could arrive during this period thus providing some cover to bombers at long distances.

Despite the imminent need to destroy the enemy before the summer of 1944 they were often grounded due to poor weather. A break came through at the end of February with a forecasted week of clear weather. This was to be the start of Operation Argument (also known as “Big Week”) targeted specifically against the Luftwaffe in order to gain air supremacy. It’s objective was to minimise the ‘Production-wastage’ differential by attacking both the factories on the ground and Luftwaffe in the air.

However, it became clear that the bombing offensive actually wasn't destroying industry at a rate where Germans could be kept up. Indeed during this period of increasing attacks German industry was put on a ‘war footing’ and increased fighter plane production despite the increase in bombing. In 1943 Germany Produced 25,500 planes. That number increased to 40,500 in 1944.

But a realization occurred to US high command - even if the Germans could replace their fighters they could not replace their experienced pilots as easily. Instead of minimizing German ‘production’ they’d focus on maximizing the ‘wastage’ of german pilots in combat. They just needed to lure the enemy up to attack the bombers with the knowledge enough would be shot down by P-51s.

This was the logic behind attacking Berlin in early March 1944. The bombers would be used more as bait for the Luftwaffe than the bombing of industry. The USAAF did so with enormous costs. The largest one day loss of the eight air forces occurred on the first Berlin Raid of march 6 1944 with 69 heavy bombers lost and known as “Black Monday”. Due to the large number of aircraft dispatched this amounted to a 10% loss rate.

These were losses the US could sustain. Luftwaffe pilot losses weren’t. After the Battle of Berlin and heavy fighting the Luftwaffe changed tactics. They would only attack en masse and other times not confront the invading bombers at all. But ultimately they ceded air control to the USAAF. The German Luftwaffe was defeated before D-Day. Or so the consensus history goes...

To look into this I gathered some data on Eight Air force missions and did some analysis.

Eight Air Force Data

The original data set came from 8thafhsoregon.com/8th/. There is an excel spreadsheet that has missions broken out between the start of operations and August of 1944. This data includes (among many things) target location, number of planes dispatched and lost for both bombers and escorts. I used this as a template and then edited it as necessary, often looking at the WWII chronology on which it was based to fix any errors (also in that link). I’ve tried to be as accurate as possible but this was a manual process so there are probably errors. I appended Latitude and Longitude to the dataset using ggmap functionality in R.

Some problems with the dataset are:

Some names of places have changed since the original. German names are now in modern day Poland for instance.

The location of dispatched planes are often ambiguous. Often there are several targets for a set of planes. I’ve no way to be sure which particular location each plane went to so I just chose one location for the lot.

After July 1944 escort by plane type wasn't broken out so I am unable to show the relative distribution of fighter types per mission.

Eight Air Force Analysis

As noted previously a key feature of bombing losses was the distance travelled to the target. The longer the distance the more likely there were

The above plot shows a scatterplot of Distance travelled by Date for a unique raid location between January 1943 and August 1944. It’s colored and numbers by percentage lossed (red is higher, blue is lower). I’ve also removed missions that exceeded 800 miles for readability as they were few in number.

One can see that loss rates decrease in both the time and increase with distance. Heavy fighting before winter of 1943 for distances more than 400 miles were particularly costly for the USAAF. These raids included Hamburg and the first two Schweinfurt Raids. One can also see a decrease in activity at the end of 1943 as weather conditions were poor and USAAF regrouped after those costly raids.

Starting in February and March the USAAF went deeper into enemy territory - a period that covered both Operation Argument and the Battle of Berlin. While these raids sustained high losses they are represented in the low teens of percentages because of the larger number of bombers attacking.

As Operation Pointblank ended focus shifted to targets in France and therefore smaller distances. In April, May, and June they attacked transportation targets, airfields, and sometimes more direct tactical support.

Overall one can clearly see that as time progressed it became less and less costly for USAAF forces to fly far into Germany as a percentage of aircraft dispatched.

Below is a plot of statistics by month to better see the aggregate losses more clearly.

The above are aggregate statistics by month for heavy bombers: total dispatched, total lost and the lost ratio.

Heavy monthly loss ratio existed prior to 1944 with a maximum of over 7% in October of 1943 (Black Thursday was the culprit). In part this was due to the small number of planes dispatched.

Starting in February the number of planes dispatched increased to a maximum in June 1944 and then slightly back down in July 1944. Total lost planes increased throughout this period as well reaching a high point in April of 1944. Even in May 1944 the USAAF lost 300 heavy bombers. In June it dropped to 200 heavy Bombers. Why was there such a drop in losses between May and June?

Looking at the increase in P-51 usage there was a sizable increase in escorts p-51 more than doubling from April (3151 to 6844) to May but only slightly from May to June. Moreover there doesn’t appear to be an obvious relationship between increased P-51 Escort usage and decrease in Heavy Bomber Losses (at least on the aggregate data - see below for further analysis).

The history I’ve described above suggested that most of the fighting was done in February and March. After this period the Luftwaffe was supposedly defeated and air supremacy passed to the USAAF. Looking at the loss ratio statistics one can see they were much more acceptable range for USAAF forces - especially compared with 1943. In some sense the Luftwaffe may have been irrelevant at that point in that the USAAF could expect replacements at that point to replace any lost bombers.

But the evidence suggests that the Luftwaffe was still inflicting heavy damage through May and didn’t cease after March as the original history suggested. What happened? I think we need to continue looking into data from the German perspective and its relative strength over time.

Luftwaffe Data

I couldn’t find similar mission-level data for the Luftwaffe during WW2. (Who knows, maybe some of that data was destroyed by the Eighth Air Force?) I did find there is a good amount of data on Luftwaffe Pilot aerial claims and planes they shot down. Pilots had strong incentives to report the planes they shot down and such claims are probably overstated. However it’s a dataset that should provide some indication of fighting strength and activity over time.

This Dataset comprises two parts.The first are the aerial claims for a pilot that includes (among other information) date, aircraft destroyed, and fighter group. The second includes data on when a pilot was removed from the war either MIA, KIA, or POW.

Ater joining these two datasets to get precise entrance (first claim in database) and exit dates there are 2,565 pilots with a total of 50,419 combined claimed victories. As the average pilot in the dataset as over 19 claims it clearly is biased towards the elite pilots and doesn’t include those pilots who had no claims. However, this could still be a useful dataset to show relative strength over time.

As an EDA I first looked at first entrances and exits by front over time. If a person transferred between fronts it would not show up in these charts. Note that I removed two entrance points from the graph as they were so extreme; May 1940 on West had 273 and June 1941 had 251 entries of pilots in the dataset. These correspond to the Battle of Britain and Invasion of Russia so we can expect a lot of pilots had their first claims during those periods.

Also Note that the West involves mediterainan, north african, and southern europe where the Eight Air Force did not generally operate. They also include night fighters targeting against English bombing raids that were somewhat distinct from the day fighters against the USAAF.

On the Eastern front one can see exits and entrance follow a seasonality pattern that corresponds to German offenses summer offenses: Invasion of Russia in 1941, road to Stalingrad in 1942, and Battle of Kursk in 1943.

For both fronts the Germans had Entries higher than existed throughout most of 1943 and early 1944. Only after the summer of 1944 were losses consistently higher than entries for both fronts.

On the Western form there was a lot of activity for the Battle of Britain - this was the Luftwaffe’s failed attempt at strategic bombing. Starting January 1944 there was a sustained increase in exits corresponding to the attrition warfare of the Eighth Air Force discussed above. While there was clear damage to the Luftwaffe during this time it reached a maximum loss of 66 pilots in July second only to losses in December 1944. If the Luftwaffe was defeated by the USAAF before D-Day then why were they losing so many pilots after that?

Luftwaffe Defeated at Normandy?

As mentioned above the Luftwaffe was a tactical air force designed to support ground offenses. German command clearly intended to use it as such during the expected Allied invasion of France as they moved a large number of Fighters towards France after June 6, 1944.

To better understand this dynamic I created an index of fighter strength by day for Reich Defense with the pilot entrance / exit and claimed data. For a particular date a pilot was included in the dataset he had claimed an aerial victory before that date and did not exit by that time. We can also see, from the most recent claim, which fighter group he was in. Using this we can tie a particular pilot to a location and therefore if he was actually under the Reich Defense.

Determining which Fighter Group and squadron were actually defending the Reich at a particular point in time was a manual process greatly helped by this website. It showed that most fighter groups defending Germany moved to France immediately after the allied invasion of Normany in June 1944. For example III Gruppe of JG 54 went from Illesheim, Germany to Villacoublay, France on June 7 1944. Moreover one can see (but not shown here) the claimed planes shot down after June 6 changed from US heavy bombers to short range english fighters (Spitfires and Typhoons) adding further evidence of the shift in priorities.

Above is a plot of the number of Pilots defending the Reich compared to all other fronts combined between Summer 1943 to October 1944. I narrowed down the Dense of Reich to those that were likely to face the Eighth Air Force in Battle so did not include fighter groups in Italy or Nordic countries. One can see it remains relatively constant up through the spring of 1944 when it actually shows an increase in the relative number of pilots. By the early summer over half of the pilots in this sample were in Defense of the Reich. It then dropped dramatically when Day Fighter forces moved to France following the invasion of Normandy.

But wait, an increase in pilots when there’s heavy attrition fighting in the first half of 1944? How is this possible?

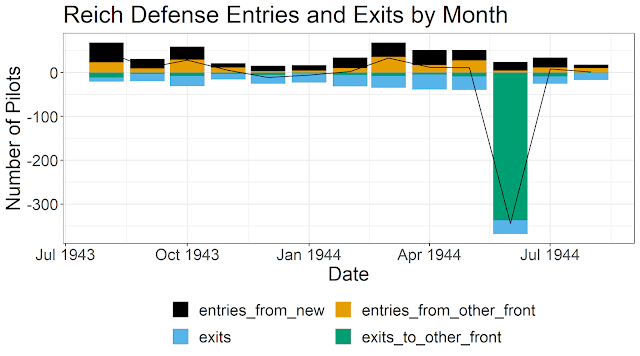

To check I created a stacked barchart by time. If the Pilots exited it counted a negative number and if they entered it counted as a positive number. One could either enter from another front or be a new pilot. They could exit to another front or exit the war entirely. (For an additional check see 2) below in the appendix. )

While there was an increase in pilots exiting throughout the first half of 1944 it appears that was offset by a combination of new pilots and reallocation of pilots from other fronts. There were few pilots exiting to other fronts until June of 1944. While it seems hard to imagine the fighting strength of the Luftwaffe increasing significantly during this time the evidence suggests that the USAAF did not destroy the Luftwaffe prior to D-Day.

Assessment of P-51

But that doesn’t mean the P-51 wasn’t instrumental in defending the bombers. I created a regression for the time period before June 5 1944 using data from the Eighth Air Force and combined it with Luftwaffe data. The response variable of interest is the number of bombers lost in combat for each unique raid.

The data generally gave precise locations of where the bombers went; it did not give similar information of where Escorts went for all missions. For example, Mission Number 367 on May 24, 1944 USAAF sent 616 bombers to Berlin and 490 bombers to French Airfields. They were escorted by 144 P-38’s, 178 P-47’s and 280 P-51’s. While USAAF would probably have sent a majority of P-51’s to Berlin there’s no way to encode that. Instead I assume an weighted percentage of fighters going to each location proportional to the relative size of the bomber fleet. In this case I calculate a weighted_p51 score of 156 (616/(616+490)*280 ) escorting the Berlin Bombers.

Using the Luftwaffe Claims Data I am able to calculate the sum of all claimed kills for pilots defending the Reich on any particular day. This is something akin to the liberty ship ‘learning by doing’ literature. I’ve found this to be the strongest predictor for any single Luftwaffe pilot data.

I include date as a continuous feature and also include dummy variables if there were no particular escorts.

Below are the results.

One can see that distance is a very important feature but that time isn’t statistically significant. This is promising as it shows there isn’t a trend that cannot be explained with features given. Also note that the total_kills variable - a proxy for strength of luftwaffe - is positively correlated and has a p-value of .06. While it’s not a strong variable in the regression it adds some credibility as a feature in general.

Of particular interest is that the P-51 is negatively correlated with a p-value of .02. This indicates that the more P-51 escorts there were the fewer the bombers lost. Interestingly we also see a somewhat positive correlation with regard to P-47’s. This could be due to the fact that Pilot’s transitioned from P-47’s to P-51’s and the regression is picking up on that trend.

Conclusions

While evidence presented here is contrary to the general story of the Air War over Europe I believe it displays a more nuanced and realistic version of events. The Eighth Air Force did not defeat the Luftwaffe but it clearly made an impact and drew resources away from other fronts - a key objective of the Pointblank Directive. Moreover it made sure the Luftwaffe was tied down in Germany and not defending France while D-Day occured. It also seems clear that the P-51 was instrumental as it allowed the Eighth Air Force to launch attacks deep into Germany while maintaining acceptable losses.

But it also seems clear that the Luftwaffe threw a large number of fighters from defending the Reich towards defending the western front and lost many pilots as a result. It wasn’t so much that the Eighth Air force defeated the Luftwaffe so D-Day could happen. Instead it seems like D-Day drew Luftwaffe resources away from Reich Defense so that the Eight Air Force could fly more freely over Germany after June 1944.

Appendix

Thought I’d just add this chart that shows the types of targets the Eighth Air Force attacked during that period. Initially U-Boats and naval sites were a large target but after they became less and less of an issue they focused more on aircraft and industrial targets in Germany in early 1944. During that time they also attacked V-Weapon sites. I thought that was interesting since it wouldn’t be until the summer when they were operational. Towards the end of the sample period they started attacking oil and even some tactical support in France.

2) As an additional check to using this data I compared the monthly exit rates by a dataset at the end of To Command the Sky (curiously they didn’t make a similar plot in their book). While the index I created using Tony Wood’s focuses on Pilots this dataset from TCTS looks at the number of planes shot down. They should be correlated and that is what we see below. However the scale of TCTS data is almost an order of magnitude higher suggesting that my index is missing a lot of data and is incomplete. I think it’s ok as a relative changes but probably not as levels

Works Consulted

Big Week: BIggest Air Battle of World War II - James Holland

To Command the Sky - Stephen L. McFarland, Wesley Phillips Newton

Engineers of Victory - Paul Kennedy

DOOLITTLE, BLACK MONDAY, AND INNOVATION - J David Rogers

How the Mustang trampled the Luftwaffe - Robert W. Courter

The P-51 Mustang: the Most Important Aircraft in History? - Marshall L. Michel

The Battle of Britain, in 1940 and “Big Week,” in 1944: A comparative Perspective - Arnold D. Harvey Github